Why I Became A Wilderness First Responder

“Uh, Dakota, I’ve got fascia showing here,” John yelled. He ditched his bike by the trail, squeezing his left forearm.

Closer inspection revealed a wide 6” long gash that John could barely hold closed. A sharp stump protruding into the trail had hacked away some serious organic material (aka arm). Blood bubbled merrily away; white fat was visible in the cut.

Three months ago, my reaction is AHHHHHH, followed by: Stammering. Fumbling. Dropping everything. I was a liability in any medical situation, whether in the backcountry or at home.

But not this day. Thanks to a Wilderness First Responder class, I was prepared.

Instructors demonstrating a head-to-toe examination on me.

Accept That Things Can Go Wrong

“Be comfortable being uncomfortable,” our instructor Mike told me during a post-class hangout. This is a guy who has climbed Denali, Mt. Rainier, and big mountains in South America over 100 times. He’s an understated badass.

Be comfortable. Being uncomfortable.

Shit happens when you’re engaged in outdoor activities like mountain biking, skiing, rock climbing, trail running and all the other sports I enjoy. People fall off bikes, tumble off a trail, take a fall climbing and slam an ankle (a college friend created a mini-epic in the Needles with that one). Stories abound.

My friend Andrew on the infamous Heinous Cling at Smith Rock. Nothing like climbing 30 feet above your last bolt. Gulp.

If we want to play outside, we must accept things can go wrong. They WILL go wrong. Sure, it’s easy to pretend all will be ok, but I’d rather prepare for that eventuality. There’s comfort readiness.

For years, I talked about taking some kind of wilderness medical training, but never made it a priority. The time. The cost. Excuses. A couple injured friends last year (one snapping an ankle on a mountain ride in Bellingham, another on a jump trail) finally pushed me over the edge. Chelsea and I both signed up for the class.

A multi-pronged rescue getting Tom off the trails after he snapped his ankle in Bellingham.

What is a Wilderness First Responder?

Enter the Wilderness First Responder (WFR) class, pronounced Woofer. In nine days and 80 hours of instruction (full-on immersion!), we went deep on wilderness medicine. The WFR is a step below an EMT certification and teaches a rigorous framework for assessing someone in need of medical attention.

From broken bones to cardiac conditions to a focused spinal assessment to psychological issues to communicating clearly via radio/phone with other medical teams, we covered hours of useful skills. Between classroom lessons, we practiced a dozen scenarios with various trauma and medical conditions, hammering home a mindset for approaching adverse situations we might encounter.

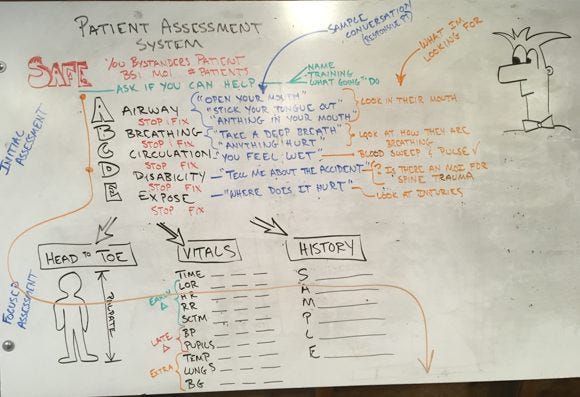

The handy Patient Assessment System (PAS).

Learning a Focused Spinal Assessment in class. We'd then practice in live scenarios.

Until recently, something as simple as Chelsea cutting her finger with a kitchen knife threw me into a tizzy. I’d rip open bandaids (usually the wrong ones) and do nothing right. WFR training teaches a process to follow, a checklist for evaluating a situation. Clear-headed, systematic confidence is at the root of their teaching.

Most scenarios were quick, 30 minutes with head-to-toe exams to practice the WFR evaluation framework. Some were more in-depth, including a mock night rescue scenario in the woods where we ended up using jackets, trekking poles, medkits - anything we had on us. We stabilized a compound fracture, handled a seizure, and stayed warm in near-freezing conditions. (Pro tip that a team member taught me: tea candles are long-burning fire starters.)

Scenarios like this were excellent for under-the-gun training.

Staying warm during a night rescue scenario. That fire was very necessary!

Takeaway: even a short hike can lurch out of control, and it’s usually at the end of the day when everyone is tired and thinking of hot food and a shower, not where their next foot placement is.

Another big simulation was a Mass Casualty Incident rescue where a Jeep and ATV collided and six people needed rescuing. We set up a a central command, coordinated with medical personnel, stabilized injuries, then hauled them around on steep, rocky terrain for rescue by helicopter.

IT WAS CRAZY. We didn’t know how many patients were out there (our instructor secretly recruited his children to be victims) or where they were. Various rescuers even “passed out” or overreacted. But the 26 students wrestled the situation under control and made it happen. All of us walked away thinking, “Hey, I can do this!”

Mass casualty incident. Our instructor's kids were convincing patients!

I Don’t Need This Crap! I Don’t Even Like the Outdoors

Many of the scenarios we talked about in class were not extreme sports accidents. A relative clearing gutters falling off a ladder at a cabin in the woods. Slips off hiking trails looking at the view (my mom did this at Smith Rock a week after the class and scared the hell out of me and Chelsea). Someone with heart problems collapsing a mile into an easy waterfall hike. A kid getting bit by a rattlesnake on a rafting trip. It could happen to you.

The WFR is for anyone who spends time in the outdoors; the rough rule is that if you’re an hour from a hospital, you’re in a wilderness scenario. If you come across someone groaning and semi-conscious on a hiking trail, you know how to help them. That’s empowering!

Practicing splinting a broken leg with typical camp supplies (jackets, sleeping pad).

Learning bandaging! This is Tagaderm, a magic breathable layer that stays on a lonnng time.

Rescue Is Far, Far Away

Maybe you’re thinking, “Why bother with this stuff when a search and rescue (SAR) team is a phone call or SOS signal away?” Good question.

Judd, a guy in our class, does underwater cave exploration as a (serious) hobby. He’s mapped never-explored caves all over the world, from the South Pacific to Madagascar. Sometimes he spends 18 hours straight underwater using an astronaut-style rebreathing apparatus. His stories of "mishaps" in scary places were a biiiit sobering.

You’d think his personal rescue story involves international waters and a foreign government. Nope! He was skiing out-of-bounds at Steamboat Springs, a day like any given Sunday. A nasty fall broke some bones (and his back). Even so close to the resort, with experienced friends, he wound up overnighting in the snow in a shattered state before a rescue team arrived. Knowing how to stabilize a situation like that is important.

SAR teams are usually volunteers. When a call or distress signal comes in, they first evaluate whether it’s an actual rescue scenario. (Often, it’s not.) If it is, they have to rally gear and people, set up a base camp, assess the situation, and get a plan rolling. When a litter or backboard is necessary, you need 18 people to form three groups of six for hauling people out. On rough terrain, it is HARD to move an injured person in a stretcher, as we found out during scenarios.

Chelsea gets hauled up steep rocks in a backboard to practice an overland carry. It's hard work!

At the end of the day, rescue is hours (or days) away. Pushing SOS on your SPOT transceiver might feel good, but knowledge for stabilizing a situation or taking matters into your own hands is key. Splinting a broken arm or taping a severely sprained ankle and hiking to the car is often faster (and definitely cheaper!) than waiting for the helicopter to show up.

As our witty instructor Dan told us, it takes Diesel Power: Dees feet got you in, dies-el get you out!

WFR in Action

Back on the trail. John holds his arm; I bust out my trail medkit. I almost forget to put on my nitrile gloves (first step before helping a patient), but remember last-second. *Snap snap*, ready to go. It takes a dozen Steristrips and some finagling to close the wound, but we get it.

GNARLY PICTURE ALERT: SCROLL PAST THE NEXT PHOTO IF YOU'RE SQUEAMISH.

.

.

.

.

.

I definitely would have freaked out seeing this before the WFR class! John's arm was gnarly. Here it is just prior to stitches after all the dressings were removed. Gnarly, yes, but better than when there was blood pouring from the wound.

A gauze bandage, plus tape wrap, and things are looking better. Final topping: John’s elbow pad, a snug cover to hold everything in place for the ride out. An hour later, he’s at urgent care getting a dozen stitches. WFR win!

What strikes me is what I didn’t do (freak out). John knew I’d taken the class and trusted that I knew how to proceed. Rather than a potentially gnarly wound bleeding profusely with miles to pedal out, we rigged a tight, secure bandage sufficient to get my buddy to urgent care.

John with his bandaged arm. To his credit, he laughed and joked through the entire bandaging process.

The backcountry is a dangerous place for us soft-bodied humans. We aren’t designed to fall, overheat, freeze, twist, bang, scrape or otherwise smack into our environment. No matter how prepared we are, there’s always risk. (That’s what makes outdoor exploits exciting!)

A couple months out from my WFR class, the maxim “Be comfortable being uncomfortable” keeps resonating. By investing in skills like wilderness medicine, primitive survival and orienteering, we equip ourselves to explore the world and push our limits in various environments.

This is for you, your friends, and any stranger you come across in need of help. I’m planning to continue my education in various outdoor skills, and I encourage you to as well. The person who needs your help in the future will appreciate it.

The WFR crew!

Resources

If you don’t have time/cash for the full WFR, check out Wilderness First Aid classes. At the very least, a CPR/basic first-aid class is worth your time. Many employers will pay for you to take the classes, especially if you work as a guide or are in the field frequently.

A few links:

The official NOLS Wilderness First Responder class schedule/location.

The less-intensive Wilderness First Aid information

For ALL the courses that NOLS offers, go here.

At the very least, make sure you have a complete medkit with you. Sure, it's best if you know how to use it, but it's better than, "um, Rick, does duct tape work as a Band-Aid?"

There are other companies and classes, but since I only have experience with NOLS, I'll stop here.

By the way, I received no compensation for this post. I wrote it because I now realize how ill-prepared I was in the past and I don’t want anyone to feel that way if something bad happens during an outdoor adventure. Here’s to excitement AND safety outside.

Rappelling off a multi-pitch climb at Smith Rock. ONWARD!